Tidal current energy devices offer potential solutions for both grid-scale power production and smaller-scale applications in areas without cabled infrastructure. However, a lack of data and information on the environmental risks of tidal current energy devices – specifically the risk of collision to marine mammals, fish, and seabirds – remains a barrier to their development. Although research indicates that many animals avoid tidal turbines, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding their behaviors close to operating turbines. To address this gap, an environmental monitoring study investigated interactions between a small-scale tidal turbine and marine animals in Sequim Bay, Washington, USA over a 141-day deployment.

Over the course of the environmental monitoring study, researchers collected and analyzed imagery from optical cameras mounted on the base of the turbine to gain insights into animal behavior in the vicinity of a small-scale tidal turbine. Data management for this monitoring effort was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Water Power Technologies Office (WPTO) TEAMER program, while analysis of the collected data was funded through a WPTO award. Notably, the study captured some of the first optical observations of seabirds and seals around a tidal turbine, offering valuable contributions to future research. Key insights and lessons learned are synthesized in Cotter et al. 2026 to support future turbine monitoring efforts and collision risk assessments.

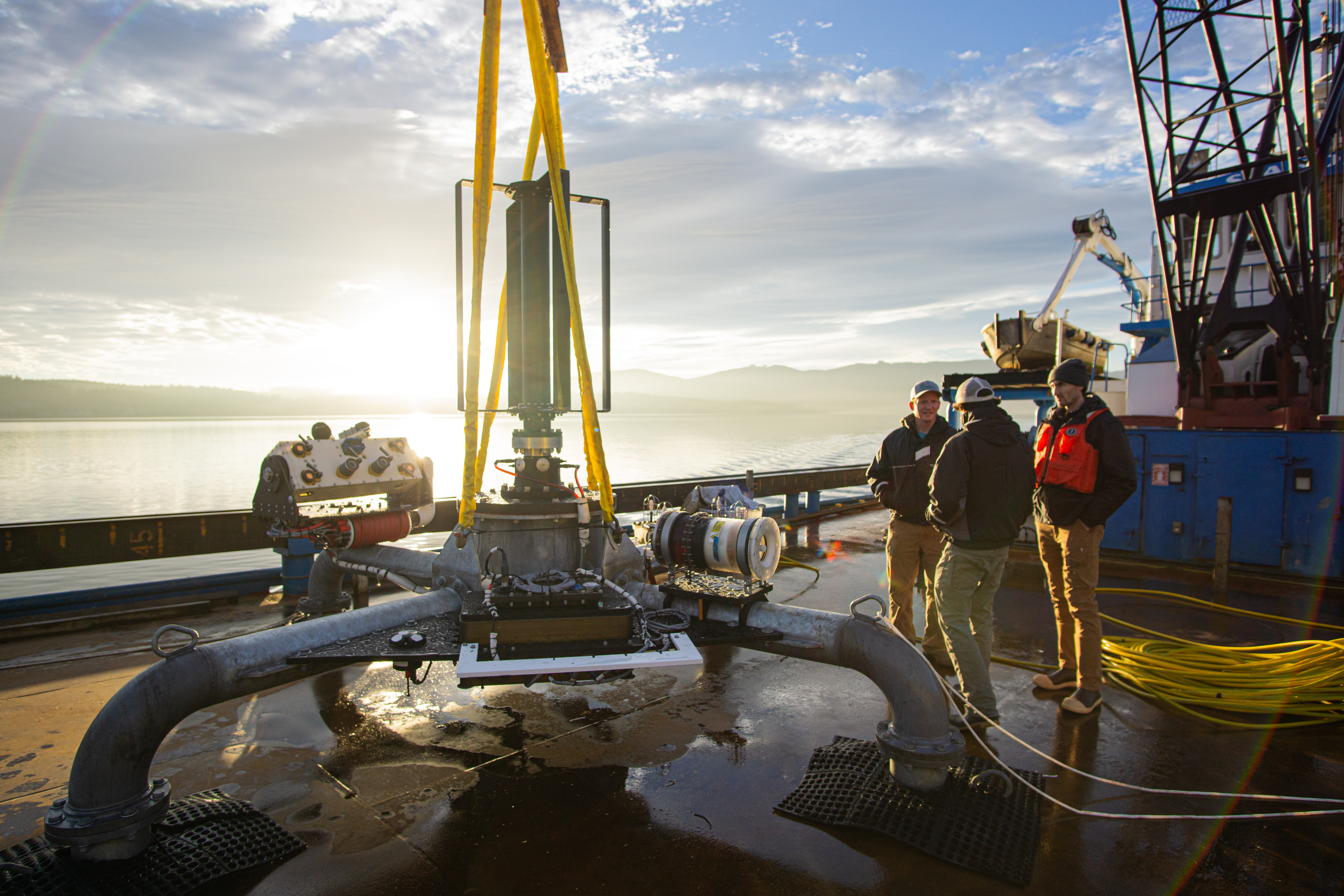

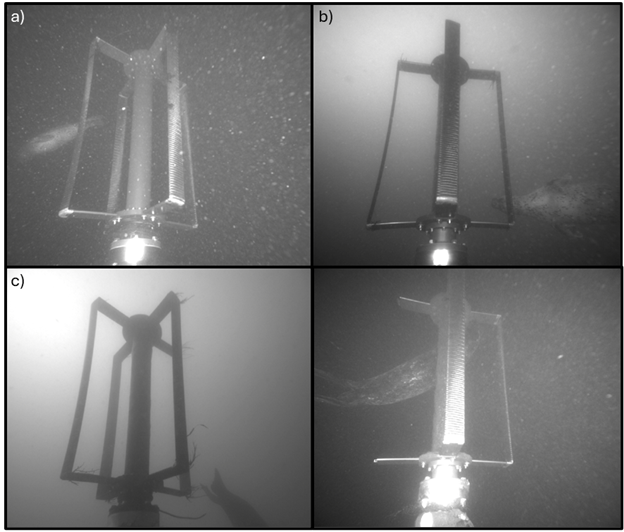

Figure 1: The Turbine Lander prepared for deployment. (Image credit: Abigale Snortland).

The tidal current energy system, referred to as the Turbine Lander, was developed and deployed with funding from the Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command’s Expeditionary Warfare Center (NAVFAC EXWC) under a Naval Sea Systems Command Contract N00024-10-D-6318 to demonstrate the feasibility of a smaller-scale tidal energy system.

The Turbine Lander features a compact 1-square-meter vertical-axis, cross-flow turbine designed by researchers at the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory (APL-UW). The Turbine Lander was designed with operational needs and environmental constraints in mind. For example, the cross-flow rotor was chosen for its simplicity and efficiency at lower tip speeds, while the gravity foundation was chosen to reduce environmental impacts to the seabed. While the Turbine Lander is relatively small, the system is considered full size as it is intended to power at-sea applications such as scientific sampling.

Figure 2: Seal swimming past the Turbine Lander in Sequim Bay. (Image: University of Washington).

The Turbine Lander was deployed on October 18, 2023, in Sequim Bay’s tidal channel, adjacent to the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s (PNNL) Marine and Coastal Research Laboratory. The channel, with an average depth of 8 meters and peak tidal velocities of 2.5 m/s, is home to a variety of species, such as harbor seals, forage fish, seabirds, and salmonids. The environmental monitoring campaign concluded on February 17, 2024.

Figure 3: Deployment of the Turbine Lander in Sequim Bay. (Image: Abigale Snortland).

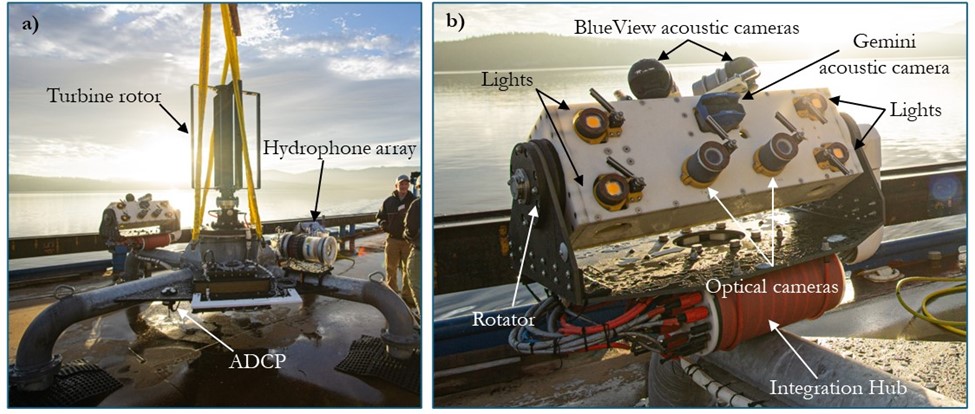

To observe animal interactions with the turbine, the research team used an Adaptable Monitoring Package (AMP), an underwater monitoring system that was developed at the University of Washington and is now commercially available through MarineSitu. This system was mounted to the Turbine Lander’s foundation and included a stereo optical camera pair and three acoustic cameras. The optical cameras allowed researchers to visually observe activity close to the turbine, while the acoustic cameras provided additional insights into animal movements outside the optical cameras’ field of view. Additional monitoring equipment mounted to the foundation included four hydrophones to monitor underwater sound and an acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) to measure flow speeds.

Figure 4: The Turbine Lander prepared for deployment. (a) Annotations of the turbine rotor and locations of the hydrophone array and Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler on the Turbine Lander’s foundation. (b) The Adaptable Monitoring Package instrument head with sensors annotated. (Images: Cotter et al. 2025).

Environmental monitoring involved both scheduled recordings (i.e., continuous data acquisition or duty cycle) and data acquisition prompted by the detection of animals by machine learning models that processed the data in real-time. Acoustic camera and ADCP data provided further context regarding species activity under various tidal conditions.

After the system was recovered, the collected optical camera imagery was reviewed and 1,044 separate events containing animal interactions with the turbine were identified. Analysis of these interactions offers valuable insights into how fish, seabirds, and harbor seals behave around an operational tidal turbine.

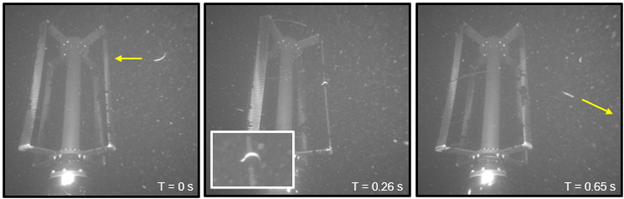

Figure 5: Example of collision between a fish and the turbine blades. The yellow arrows approximate the direction the fish was moving in a given frame, and times are presented relative to the first frame. The inset in the middle frame shows a larger view of the collision seen on the blade on the right-hand side of the image. (Images: Cotter et al. 2025).

A total of 299 fish encounters were recorded while the turbine was rotating, although it is likely that the monitoring equipment did not capture the full extent of fish activity in the area and fish were undercounted. Fish behaviors included drifting passively past the turbine, swimming away from the turbine to avoid collision (evasion), and four direct collisions with the rotating turbine blades. In all but one case the fish swam away following the collision. Interestingly, two of the observed collisions were related to predator-prey interactions when seals had chased the fish towards the turbine.

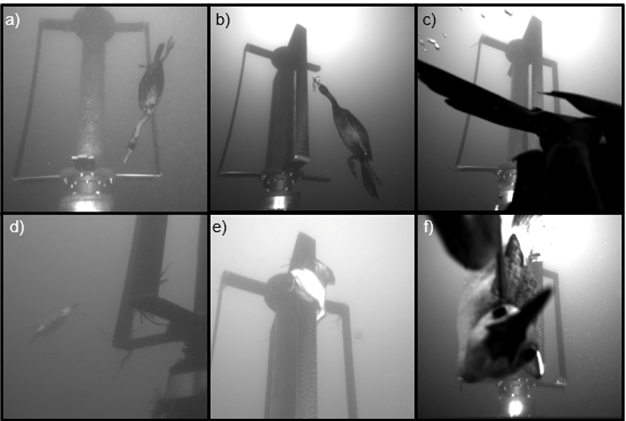

Among 406 observations of seabirds, none were observed while the turbine was rotating, and no collisions with the turbine were observed. Diving seabirds were only observed during the day, and were most frequently observed at high tide. Only two seabird sightings occurred when tidal currents were fast enough for turbine operation (above at 0.9 m/s), but in both cases, the turbine was powered down.

Figure 6: Examples of seabirds. (a-c) Cormorants diving, swimming to the surface, and presumably foraging in the vicinity of the AMP. (d-f) Pigeon guillemots swimming, picking at the rotor, and interacting with the AMP. (Images: Cotter et al. 2025)

Harbor seals were also observed. Of the 92 seal sightings, most were seen near the turbine when it was stationary (90%) and at night (58%). When seals were observed in the vicinity of the moving turbine, some approached the turbine but demonstrated strong swimming capabilities, and no collisions were observed. In scenarios where seals were observed chasing fish prey in the vicinity of the turbine, they stopped upon encountering the turbine and redirected to avoid collision.

Figure 7: Examples of seals. A) Seal swimming behind the moving rotor at night. B) Seal approaching the moving rotor in the wake during the day. c) A seal diving towards the seabed. d) A seal entering the rotor’s swept area and bending around the shaft. In both (c) and (d) the rotor was stationary. (Images: Cotter et al. 2025)

The Turbine Lander was recovered on March 7, 2024, marking the conclusion of its 141-day deployment in Sequim Bay. Valuable data and insights into animal behavior near operational turbines were gained, supporting both future monitoring efforts and more effective collision risk assessments. Additionally, the operational and performance data collected during the Turbine Lander’s deployment are instrumental to the advancement of small-scale tidal turbine technologies.

Key Insights and Lessons Learned

- Optical cameras installed on the Turbine Lander’s foundation provided high-resolution data on animal interactions close to the turbine.

- Because sampling methods were varied over the course of the deployment based on lessons learned, the dataset did not lend itself to quantitative analysis of avoidance or collision rates, the observed animal interactions provide new insights into animal behavior around a turbine.

- Automatic detection algorithms can effectively detect animals and reduce data volumes and human review effort, but their effective implementation requires careful attention to model validation and sampling schemes.

The environmental monitoring study in Sequim Bay directly contributes to the responsible development of tidal current energy at both grid- and small-scales. By providing data on fine-scale animal interactions with an operational tidal turbine, the study helps to address key uncertainties regarding collision risk. Additionally, lessons learned regarding automatic optical detection algorithms, monitoring equipment selection and limitations, and monitoring in less-than-ideal conditions provide essential information for improving the effectiveness of future monitoring efforts.

Learn more about the environmental monitoring campaign in Cotter et al. 2026, read about the sonar data in Bassett & Cotter 2025, access the optical and sonar records of animal interactions in Bassett & Cotter 2024, and review lessons learned from the design and operation of the Turbine Lander in Bassett et al. 2024. More information about the AMP is available in Polagye et al. 2020.